Nature has been sending us some very powerful messages lately that our current way of relating to ecosystems is not working in some very significant ways.

I was reminded of that on June 16, 2020 when I heard that a wildfire —whose burning birth was visible from my camphouse porch three nights ago as its glow was reflected by the sky — had doubled in size to more than 100 square miles.

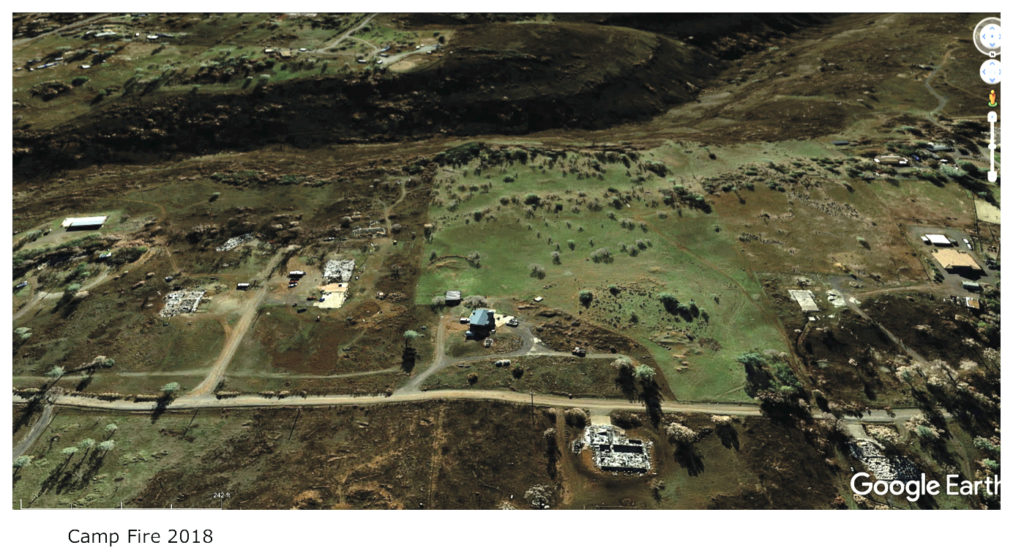

That inspired me to re-post an observation I made on this website not too long ago. That observation came after the 2018 Camp Fire near the California Town of Paradise described as ”the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history to date.” This 153,000+ acre wildfire raged in and around the central California town of Paradise from November 8 to 25, 2018 and resulted in 86 deaths and destroyed nearly 14,000 residences.

Science and firefighters tell us that recently, wildfires have increased in size, severity, and frequency. What’s more, the trend is likely to continue, says a recent article in the Washington Post. Why and how is this happening? An answer to that very important question is offered by no less than Nature herself. How does she answer that question? By offering alternatives offered side by side and thus giving us the opportunity to choose. Those side by side alternatives reveal how different types of human management can make the land more (or less) fire prone. In fact, one of those communications comes from the Camp Fire itself. Here’s how…

When C. J. Hadley, the editor of Range Magazine, (for which I have written a number of atrticles including one on this topic) learned I was working on this topic, she forwarded to me a couple of photos of the Camp Fire burned area sent to her by a reader who had downloaded them from Google Earth. The photos appeared, rather clearly, to show that the Camp Fire had stopped at a fence that enclosed an area that had apparently been grazed, after burning the un-grazed area outside the fence. Inside the fence, on the area that had apparently been grazed, the grass was green and unburned. So was the house included within that area. Outside of that fence, on the area that appeared to have been ungrazed, almost everything had burned — not only grass, trees, and bushes, but most of the houses and other structures.

Here’s the photo again:

What stopped the fire on the straight line created and enclosed by the fence? Not the fence wire. Wires, barbed or woven, can’t stop a raging windblown wildfire. What stopped the fire had to be the difference of the condition of the land on the two sides of the fence — a difference of condition that could stop — had stopped — a raging wildfire as effectively as a wall of water.

Checking various sources I found other evidence that wildfire has burned an area of rangeland and stopped right where grazing began. Among these are photographs from a US Geological Survey report on the Murphy Wildland Fire Complex (2007) in Idaho and Nevada. The photos were taken by, among others, Karen Launchbaugh, Professor of Rangeland Ecology and Director of the Univ. of Idaho Rangeland Center in Moscow, Idaho. and W. Butler, with the US Forest Service.

Below is another fenceline firestopper photo downloaded from the Realtors Land Institute website:

According to Paul Bottari of Wells, NV., Member of the REALTORS® Land Institute 2017 Government Affairs Committee, the 6,000 acre unburned field on the left in the photo had been grazed by about 150 to 200 cattle six weeks before a fire was ignited by an electrical transformer and burned across an adjacent field that ”hadn’t been grazed yet.” ”Then when the fire reached our fence,” wrote Bottari, ”it stopped except where there were a few stringers of high grass still remaining.” (visible in the photo)

Add another even more dramatic fenceline firestopper photo from Zak Miller on GrazeItDon’tBlazeIt.com…

This leads to an obvious question. Could the set of conditions on the unburned side of these fences be reliably duplicated? If it can, you know there are plenty of people who would want those conditions to be duplicated on their side of the fence or property line or at least on an area near and around their home. That means we appear to have stumbled onto a marketable service here — grazing as a fire prevention/neighborhood protection tool.

Actually, this tactic is already being used in a number of places. Goats have been used for some time to graze land surrounding the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Plant in California to reduce the danger of wildfire.

I don’t know if there is any real connection to this (admittedly it’s been a while), but I’ve given a couple of talks at Chico State University (about 15 miles from Paradise) about how grazing can be used to sustain and even restore ecosystem health. One of the things I included in that discussion was how the impact of animals (cows and goats) grazing the land can reduce fire danger. A month before the Camp Fire ignited, the city of Chico, California, imported a number of goats to begin a month-long grazing program to reduce fire danger in one of the city’s parks. The Camp Fire burned to Chico’s edge but, according to the fire map, barely entered the town and didn’t really get near the park.

Also, about 96 miles from Paradise, the town of Nevada City, California (where I have also given talks), has created a Goat Fund Me page. That’s right. I didn’t misspell it. The gofundme.com page is named ”Goat Fund Me” and is being used to raise money to hire goat ranchers to use their animals to clear flammable brush and grass from a 450 acre greenbelt that surrounds that town.

Would it work? Does anyone believe it will work? One item of evidence is the fact that the Vice Mayor of Nevada City, Reinette Senumm, says the town is using ”Goat Fund Me” to raise money quickly because the goats are only available on the short term. Why? They’ve already been hired out for fire prevention to other municipalities the rest of the year.

Add to this the fact that goats aren’t the only grazing firestoppers. Cattle achieved some of the successes illustrated above. That means wildfire prevention could play a significant role in keeping a lot of American ranches and ranchers in business, so they don’t have to sell out to subdivisions. In fact, it’s a ranching product even vegans can love. One rancher who offers this service said he tells vegans and vegetarians: ”After you train your workers, I understand that you might not want to eat them!’”

“But, wait a minute!” I know some of you are protesting, “How can grazing stop a wildfire, except by having the animals eat everything burnable! But that causes overgrazing, which accelerates climate change, which causes more fire!”

The photo below, downloaded from a website regarding the use of grazing to promote ecosystem health — Holistic Management International, shows a ranch in Australia that provides an answer to that question. As Allan Savory, who originated HMI, has deservedly become known for pointing out — when livestock grazing is conducted in a manner that mimics the evolved interaction of humans and other natural predators with wild grazers and the plants they graze, it actually stimulates the life functions of the plants, enabling them to retain more moisture, which makes them more resistant to wildfire. That appears to be the case not only while they’re re-growing and green, but even when they’ve gone to seed and become dormant and brown. The photos above show some areas in that condition that appear to have resisted wildfire.

Viewing the Australian ranch photo I believe you can get an idea of how grazing can stop wildfire at a fence line by making the land on the grazed side too green and healthy to burn. Also, while we’re talking about Climate Change, the reason those plants on the grazed side are so green is because they are growing, and as they grow, are re-grazed, and re-grow they pump carbon out of the air and into to the soils and the grazing animals that feed on them.

Carbon sequestering, too?!

That means, grazing is not only an effective tool against wildfire, it sequesters carbon and combats Climate Change too. To me, that means ranchers should be soliciting contributions for fighting global warming as well as for making the West more resistant to wildfire. You guys are going to get really rich! As rich as environmentalists! (Check ”Eco-Profits,” the previous post that sheds more light on this matter. )

Time to start a ”Go Fund Moo” page

Hearing what I’ve just told you, a friend said, ”Wildfires are still going to happen, you can’t graze everyplace!” Aware of this limitation, some ranchers and ranching groups have adopted the tactic of creating firebreaks by grazing. That way they can use temporary fences and/or herders to focus grazing around the most valuable, most vulnerable areas to make them more fire proof without ”grazing everyplace.” (That’s what Nevada City and Diablo Canyon are doing.)

Last, but certainly not least, all of this raises one more very important issue — maybe the most important… If grazing works to limit wildfire as well as the above illustrations seem to indicate, removing grazing from open country ecosystems apparently makes those areas significantly more susceptible to wildfire. This is especially the case in areas that include grasslands and almost all do. From this it seems to follow that removing grazing from wildfire vulnerable areas could be extremely unwise, even hazardous. In fact, it might even make those who are responsible for that removal accountable and liable for damage thus caused, including loss of homes and even lives.

Note: Another prior post that sheds light on this topic is: FIRE DANGER IN MY NEIGHBORHOOD?!!!