It’s been very, very dry, where I live in Arizona, but one day after it rained pretty hard, I logged on to the web to check the news concerning the weather to see if it was going to rain again the next day. When I got to the weather website I got a real surprise, however. What I saw was a video of a car being washed down a suburban street by heavy swirling floodwaters and bouncing off other parked vehicles along the way. The article accompanying the video said several neighborhoods in Flagstaff, Arizona — 30 miles from where I live, had experienced two days of serious flashflooding caused by heavy rain falling on a nearby area of National Forest that had been devastated by a wildfire tow years before, in 2019.

It’s been very, very dry, where I live in Arizona, but one day after it rained pretty hard, I logged on to the web to check the news concerning the weather to see if it was going to rain again the next day. When I got to the weather website I got a real surprise, however. What I saw was a video of a car being washed down a suburban street by heavy swirling floodwaters and bouncing off other parked vehicles along the way. The article accompanying the video said several neighborhoods in Flagstaff, Arizona — 30 miles from where I live, had experienced two days of serious flashflooding caused by heavy rain falling on a nearby area of National Forest that had been devastated by a wildfire tow years before, in 2019.

The article continued: ”On Tuesday (& Wednesday), residents of the city’s east side neighborhoods had debris, water, mud and more come down their streets. This was the first time since the fire burned (in 2019) that those residents experienced flooding from the burn scar.”

That certainly got my attention for a number of reasons. First, the flood and the fire had happened in my old home town — Flagstaff, where I lived from 1980 to 2004, and not far from where I live now in Sedona, AZ.

A more awakening and alarming aspect of the shockingly severe burnscar flash flood, however, comes from the fact that, in the first 7 1/2 months of 2021, 480,000 acres (750 sq. miles) of Arizona has burned in wildfires. According to the National Interagency Fire Center (also 12News), that’s more than the acreage burned in Alaska, New Mexico, California and Oklahoma — the next four most-burned states combined. To boot, 978,519 Arizona acres burned in 2020.

In light of that, it seems undeniable that Arizona is facing the possibility of alarming amounts of after-wildfire damage such as the spectacular flash flood that made headlines in Flagstaff . That possibility has been the subject of warnings in a number of other communities as well, and it is especially awakening to my wife and I (and our neighbors) because we live in an area surrounded by the kind of landscape that has been burning in those wildfires — rangelands and dispersed forest mostly owned by the government. In fact, just 9 or 10 miles over the hill from my house, the Rafael Fire burned 121 square miles (78,065 acres) last month.

Alarmed by that, my wife and I have watched and wifi’ed many, many news reports on Arizona’s wildfire explosion paying special attention to the warnings about the other forms of damage and danger that can result from extensive wildfires. Flash floods especially catch our attention because we live only a few yards from a stream called Dry Creek, which we watched swell from a few inches deep to more than 12 feet deep during a flash flood three years ago, going over the bridge leading to our house rather than under it.

This brings to mind a couple of very important questions. First, How many and what kind of problems of this sort can and very likely will result from wildfires as extensive as the ones Arizona has experienced?

A good answer to that question, however, actually depends on the answer to a more important question — a question I wrote this post to provide an answer to…

What can we do to reduce or even avoid the associated or resultant damage caused by wildfires, even extensive ones?

Fortunately, I know someone who has developed and tested an answer to that question which was notably successful — an answer I’m happy to share with you, and you might want to take note of. That person is Terry Wheeler, a rancher, biologist, ecologist and innovator whose solutions to extremely difficult ecological problems have been featured in other posts on this website, including:

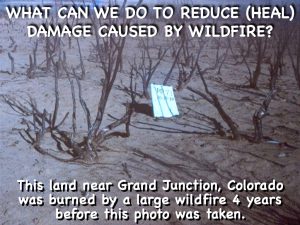

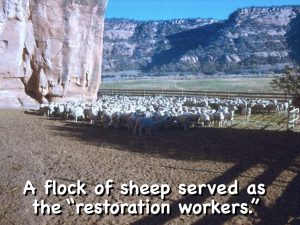

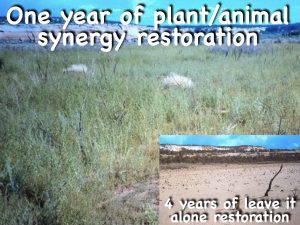

There is probably no better time than now, especially in fire-prone Arizona, to take a look at images Terry Wheeler has provided illustrating and explaining the successful application of an effective answer to the question: What can we do to reduce post-wildfire damage? Actually, Terry would probably say the best way to reduce post-wildfire damage is to heal burned areas in a way that not only reduces or even ends wildfire’s derivative, devastating impacts but significantly reduces the likelihood of those, and other, areas burning so extensively in the future.

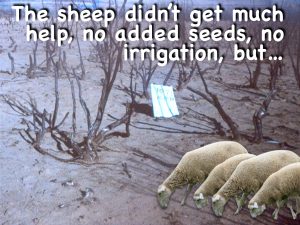

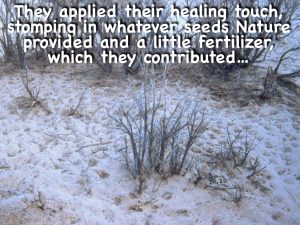

Check the example shown in the gallery below. The plant/animal synergy interaction applied by Terry Wheeler (and shown in these photos) transforms a wildfire damaged area that has remained damaged and ready to create burnscar flooding and catastrophic erosion for 4 years and turns it into a green growing, living plant area that is resistant to flood-creating runoff and moist enough to resist fire.

After looking at those phots, if you find yourself doubting that grazing animals can synergise with plants sufficiently to create this kind of effect, check a number of other posts on this website that show even more dramatic evidence of this eco-healing interaction. And, after you check those posts ask yourself, what would you like to live in the vicinity (downstream) of — an area regreened as these have been? Or a slow healing burnscar susceptible to severe erosion or some other natural deterioration?

A good post with which to start your investigation is:

AN EFFECTIVE, ECONOMICAL, NATURAL WAY TO RESTORE VERY DAMAGED LAND

Another good one is:

SIERRA CLUB GETS ”LEARNIN’S BETTER THAN BURNIN'” — TOUTS FIRE-EATING GOATS

&